You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Gripe alert - metal stamping!

- Thread starter NINEX19

- Start date

A lot of people misinterpreted the language and have been mad at Ruger for 20 years over nothing.

No, not mad at Ruger or anyone else, but just speculating on why they may have added all the verbiage to the guns. Personally I don’t get too upset at these companies when they make some of these difficult decisions. I realize that often they have to choose the least objectionable of several bad options. So, I shoot my Rugers with the extra stampings, my S&Ws with the Hillary Hole and collect all those trigger locks in box. At the end of the day these things are just the reality of the litigious society in which we live.

Driftwood Johnson

Thank you for the pictures and the detailed explanation. Those were very helpful for time frame and further explanation of the warning label.

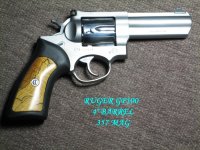

I get it. I know why they stamped the warning. The Ruger GP100 just happened to be my last acquisition that is taking the brunt of the criticism. This was more of a general gripe about all makers plastering almost all clean space on their guns with some type of witting, whether it is necessary or not. Location and the size of font they choose to use are not the best in my opinion.

MY gripe was that I would just like to have a gun with some clean lines and surfaces that does not detract from its eye appeal. I was not wanting this to turn into a "why does Ruger put a warning label on its guns" thread. I know much of this is the gun makers prerogative and if I don't like it, I do not have to buy it. I am just venting, not protesting.

On a side note, Driftwood Johnson, you say that you "can't believe some of the things that gun owners complain about". It looks like your from the "land of the Pilgrims". I am not sure what state you are trying to reference, but my assumption would be Massachusetts. Ironically, this is one of the most regulated states for gun ownership in the U.S. Perhaps if all gun owners stop "complaining", we will all be left with draconian and unconstitutional laws like they have in Massachusetts. This is not a personal attack on you, it is just a general observation about how we can all come to accept what is the normal way of things over time based on the society around us.

Thank you for the pictures and the detailed explanation. Those were very helpful for time frame and further explanation of the warning label.

I get it. I know why they stamped the warning. The Ruger GP100 just happened to be my last acquisition that is taking the brunt of the criticism. This was more of a general gripe about all makers plastering almost all clean space on their guns with some type of witting, whether it is necessary or not. Location and the size of font they choose to use are not the best in my opinion.

MY gripe was that I would just like to have a gun with some clean lines and surfaces that does not detract from its eye appeal. I was not wanting this to turn into a "why does Ruger put a warning label on its guns" thread. I know much of this is the gun makers prerogative and if I don't like it, I do not have to buy it. I am just venting, not protesting.

On a side note, Driftwood Johnson, you say that you "can't believe some of the things that gun owners complain about". It looks like your from the "land of the Pilgrims". I am not sure what state you are trying to reference, but my assumption would be Massachusetts. Ironically, this is one of the most regulated states for gun ownership in the U.S. Perhaps if all gun owners stop "complaining", we will all be left with draconian and unconstitutional laws like they have in Massachusetts. This is not a personal attack on you, it is just a general observation about how we can all come to accept what is the normal way of things over time based on the society around us.

I am not sure I see a connection between complaints over relatively minor issues like markings on a gun and opposition to gun control laws. AFAIK, the markings might offend some kind of aesthetic sense, but do not involve our constitutional rights.

I don't see that marking as being the "gun maker's prerogative" but as being forced on Ruger as a condition for settlement of a lawsuit. If you can't understand the difference, then perhaps you should have an attorney explain it to you. You certainly have the choice of not buying any more Ruger firearms if they offend your sensibilities that much, but I shall continue to do so. As Jim Watson says, you can't see the markings when firing the gun.

Jim

I don't see that marking as being the "gun maker's prerogative" but as being forced on Ruger as a condition for settlement of a lawsuit. If you can't understand the difference, then perhaps you should have an attorney explain it to you. You certainly have the choice of not buying any more Ruger firearms if they offend your sensibilities that much, but I shall continue to do so. As Jim Watson says, you can't see the markings when firing the gun.

Jim

James K,

Please consider what I said in the previous post:

This thread has gone way off what the intention of the OP was. Once again, this is not about Ruger specifically, nor their past, nor their legal requirements, nor the "instructions and warnings". This is about ALL guns and makers and what seems to be the increasing, obnoxious printing, and other markings that detract from the aesthetic appeal. Yes, most of this IS the gun makers prerogative.

Don P, Thanks, That looks great. I will look into this more. If cost is too much, I am fine with they way it is for a utility type gun.

Please consider what I said in the previous post:

MY gripe was that I would just like to have a gun with some clean lines and surfaces that does not detract from its eye appeal. I was not wanting this to turn into a "why does Ruger put a warning label on its guns" thread. I know much of this is the gun makers prerogative and if I don't like it, I do not have to buy it.

I was not trying to connect complaints on "minor issues" with gun control laws. The connection I was trying to make was the snowball effect. If people see things as minor issues and allow them a pass, larger issues build on them and pretty soon that is the new normal and everyone accepts it without issue. If gun-makers get the word that owners prefer not to have excess wording and large print on their guns, and it might cost them sales, then they might change how they design in the future.I am not sure I see a connection between complaints over relatively minor issues like markings on a gun and opposition to gun control laws. AFAIK, the markings might offend some kind of aesthetic sense, but do not involve our constitutional rights.

This thread has gone way off what the intention of the OP was. Once again, this is not about Ruger specifically, nor their past, nor their legal requirements, nor the "instructions and warnings". This is about ALL guns and makers and what seems to be the increasing, obnoxious printing, and other markings that detract from the aesthetic appeal. Yes, most of this IS the gun makers prerogative.

Don P, Thanks, That looks great. I will look into this more. If cost is too much, I am fine with they way it is for a utility type gun.

I have an old early 1980's M77 6mm Rem that I have always thought was a very pretty classic styled bolt rifle. Even with the script on top of the barrel. I do understand though that some people don't care for this, blame ignorant people for this, not Ruger. The mistakes of a few always seem to effect the responsible majority.

NINEX19, I'll take that Redhawk please!

NINEX19, I'll take that Redhawk please!

Car dealers attach after drilling a hole then charging you to advertise for them.

"...this litigious society..." Yep. As I recall, Ruger has faced multiple frivolous law suits over the years. Not only has it caused the ugly markings, but it has led them and every other firearms manufacturer to sell their stuff with crappy triggers, etc.

"...this litigious society..." Yep. As I recall, Ruger has faced multiple frivolous law suits over the years. Not only has it caused the ugly markings, but it has led them and every other firearms manufacturer to sell their stuff with crappy triggers, etc.

Well, go back a hundred years and look at a Colt M1911 and read all the patent dates stamped across the left side of the slide.

It is not the only one, but it was a Government pistol. Who was going to steal the patent? Publishing the patent dates does not help it shoot any better nor do the patent dates on old clocks from two hundred years ago help you tell the time.

Cigarette warnings do not appear to stop smokers who absolutely know tobacco kills them and others around them. We fail to stamp out stupidity.

It is not the only one, but it was a Government pistol. Who was going to steal the patent? Publishing the patent dates does not help it shoot any better nor do the patent dates on old clocks from two hundred years ago help you tell the time.

Cigarette warnings do not appear to stop smokers who absolutely know tobacco kills them and others around them. We fail to stamp out stupidity.

. The Civilian editions was a 1911 and the serial number began with a C followed by the numbers of the SN.

1911 and 1911A1 are the military designations, and while commonly used to identify them in conversation, the guns that Colt built and sold to the civilian market were not 1911s. They were "Government Models", and so marked.

Driftwood Johnson

New member

Howdy Again

Markings on Firearms are very important, particularly to the collector.

As mentioned, the patent dates on the 1911 are the patents that Colt bought from John M Browning when they decided to manufacture the pistol. Some of these patent dates go much farther back than the 1911, back to ideas that Browning patented on much earlier guns. And let's not forget the government inspector's cartouche, GHS for Gilbert H Stuart.

When Daniel Wesson was a young man he worked for his brother Edwin, a manufacturer target rifles. Daniel learned two very important financial lessons from his brother. He learned the importance of securing patent rights. And when Edwin died suddenly and everything in the shop, including Daniel's tools, were seized by creditors, he learned to never over extend himself financially.

Years later, when Wesson partnered with Horace Smith to form Smith and Wesson, he developed a design for a small cartridge revolver that could be loaded with cartridges from the rear, a vast improvement over the Cap & Ball revolvers of the day. But when they did a patent search, Smith and Wesson discovered that a man named Rollin White had already patented the idea. They approached White and attempted to buy the patent from him. White refused to sell the patent rights, but instead agreed to license Smith and Wesson to produce revolvers using the technology he had patented, for a royalty of 25 cents for every revolver S&W produced.

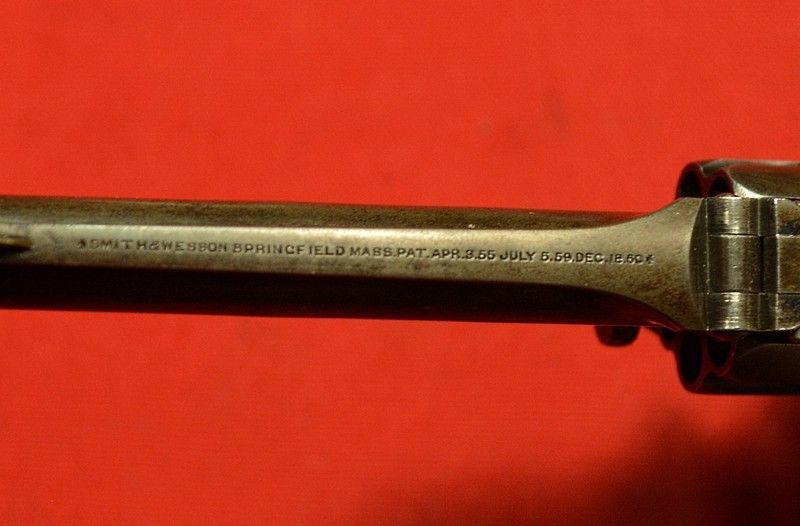

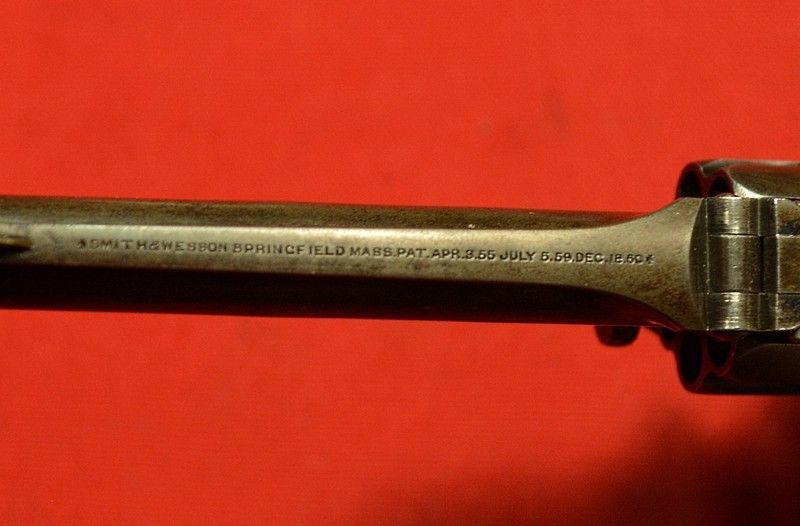

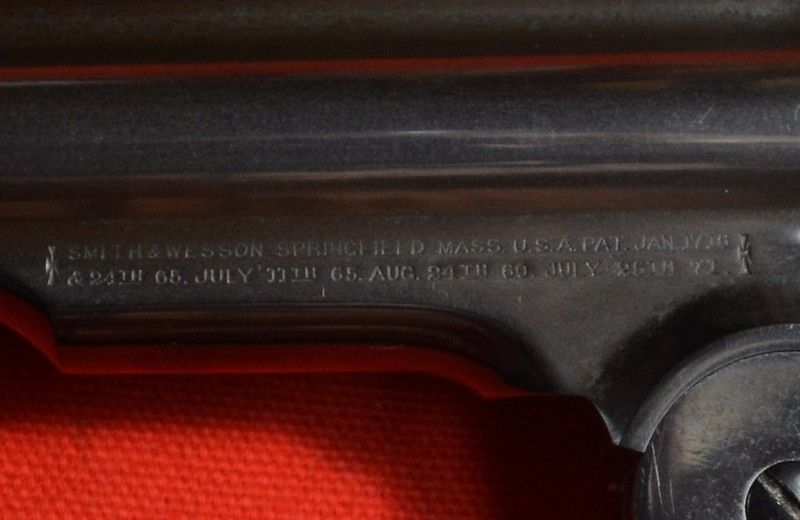

The April 3, 1855 patent date on this little S&W No. 1, 3rd Issue represents the White Patent. Securing patent rights this way, and stamping them on the gun gave S&W exclusive rights to produce cartridge revolvers in the US all through the Civil War, when all the other manufacturers, Colt included, were only able to produce Cap & Ball revolvers. And clever old Daniel had written into the contract that it was White's responsibility to pursue patent violators. White died a poor man, while Wesson became rich.

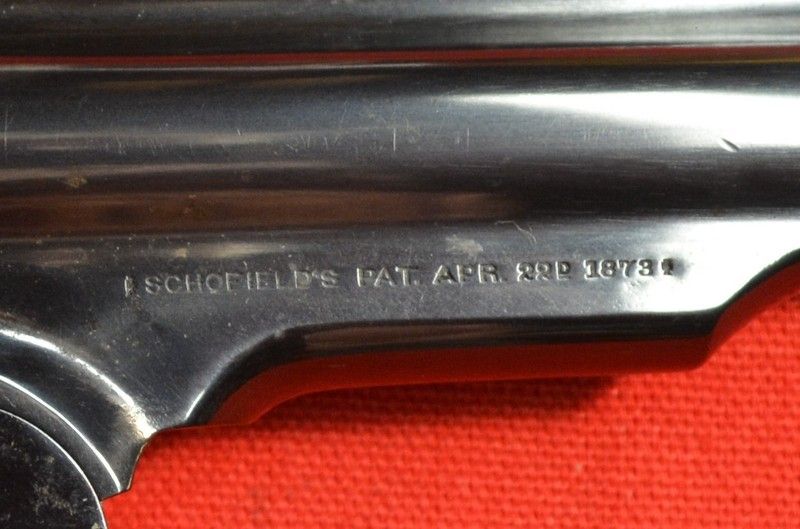

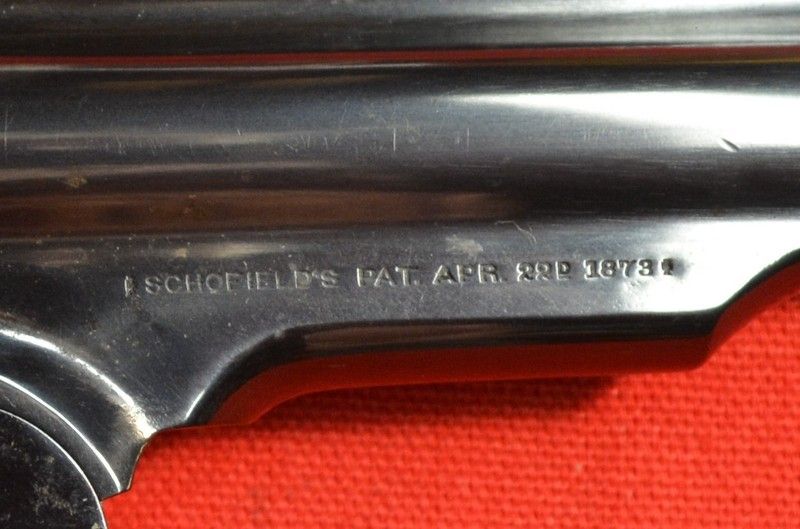

Another important aspect of markings is being able to detect refinished firearms. This Schofield revolver has been refinished. It was professionally refinished, but it can be seen how the refinisher polished the steel a little bit too much, causing the markings to become slightly indistinct. Being able to recognize a refinished gun can save the buyer a great deal of money.

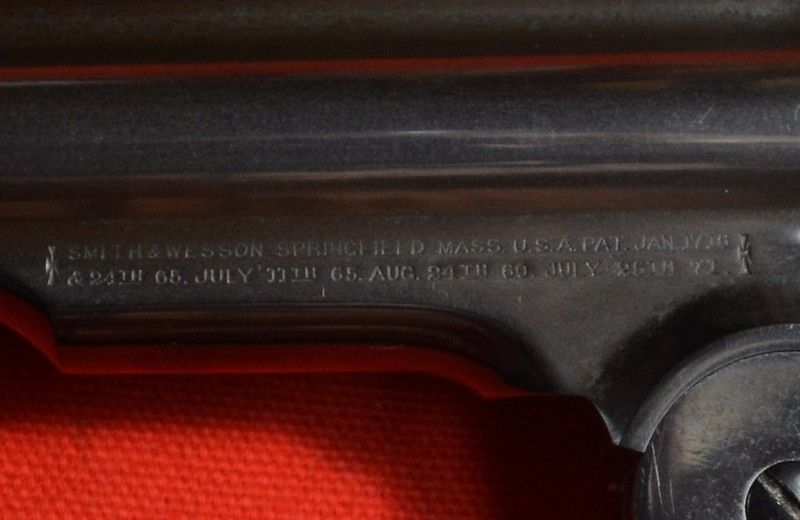

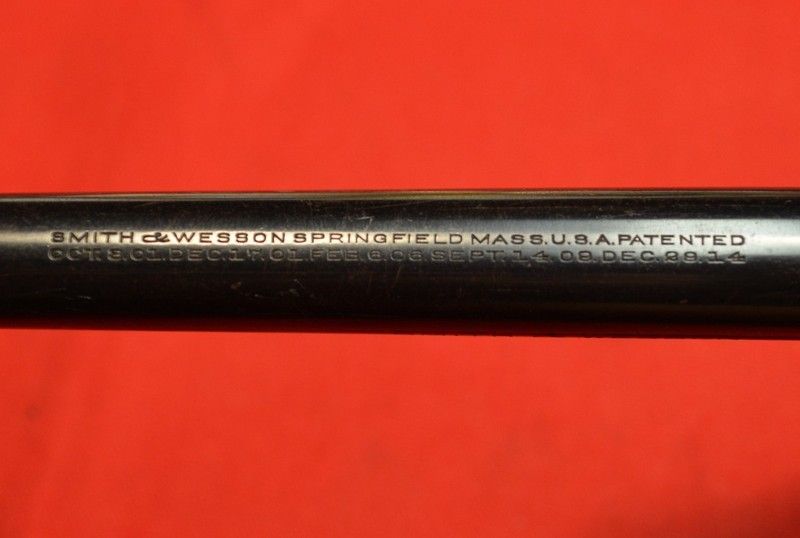

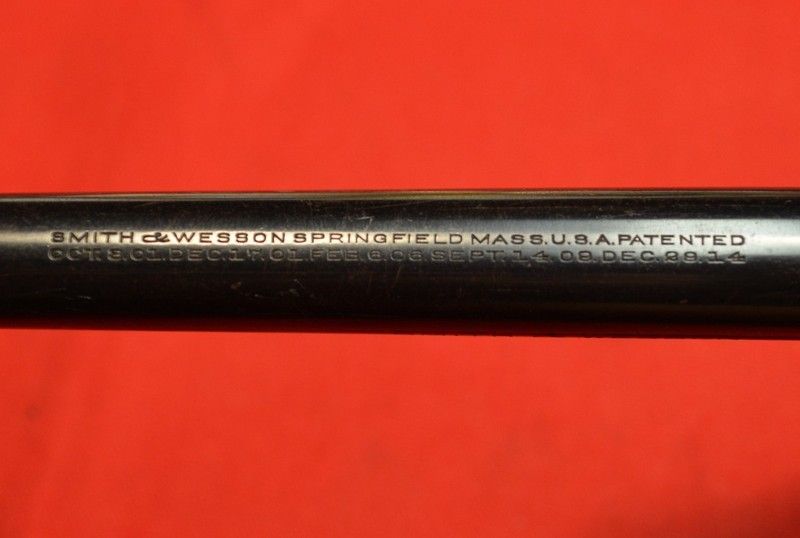

As patents expire, they are no longer stamped on firearms. These are the markings on a M&P Target Model that shipped in 1917.

Smith and Wesson was fierce about protecting their patents. There were unscrupulous firearms manufacturers in Europe who copied their designs and even forged the Smith and Wesson name on their cheap copies. S&W could not do much about international trade violations, but they could influence what could be imported legally.

Patents expire over time. Trademarks do not. In the 1920s and 1930s inexpensive copies of Smith and Wesson revolvers, mostly manufactured in Spain, were flooding the American firearms market. S&W was able to trademark the color Case Hardening process that they used on their hammers and triggers to prevent cheap copies from being imported.

So, there is a lot more than simple vanity involved in marking firearms. It can be fascinating to study what is revealed by the markings on a firearm.

The one that I have was made in 1918. It does not say Government Model on it anywhere. Instead, on the right side of the slide it says COLT AUTOMATIC CALIBRE 45.

Markings on Firearms are very important, particularly to the collector.

As mentioned, the patent dates on the 1911 are the patents that Colt bought from John M Browning when they decided to manufacture the pistol. Some of these patent dates go much farther back than the 1911, back to ideas that Browning patented on much earlier guns. And let's not forget the government inspector's cartouche, GHS for Gilbert H Stuart.

When Daniel Wesson was a young man he worked for his brother Edwin, a manufacturer target rifles. Daniel learned two very important financial lessons from his brother. He learned the importance of securing patent rights. And when Edwin died suddenly and everything in the shop, including Daniel's tools, were seized by creditors, he learned to never over extend himself financially.

Years later, when Wesson partnered with Horace Smith to form Smith and Wesson, he developed a design for a small cartridge revolver that could be loaded with cartridges from the rear, a vast improvement over the Cap & Ball revolvers of the day. But when they did a patent search, Smith and Wesson discovered that a man named Rollin White had already patented the idea. They approached White and attempted to buy the patent from him. White refused to sell the patent rights, but instead agreed to license Smith and Wesson to produce revolvers using the technology he had patented, for a royalty of 25 cents for every revolver S&W produced.

The April 3, 1855 patent date on this little S&W No. 1, 3rd Issue represents the White Patent. Securing patent rights this way, and stamping them on the gun gave S&W exclusive rights to produce cartridge revolvers in the US all through the Civil War, when all the other manufacturers, Colt included, were only able to produce Cap & Ball revolvers. And clever old Daniel had written into the contract that it was White's responsibility to pursue patent violators. White died a poor man, while Wesson became rich.

Another important aspect of markings is being able to detect refinished firearms. This Schofield revolver has been refinished. It was professionally refinished, but it can be seen how the refinisher polished the steel a little bit too much, causing the markings to become slightly indistinct. Being able to recognize a refinished gun can save the buyer a great deal of money.

As patents expire, they are no longer stamped on firearms. These are the markings on a M&P Target Model that shipped in 1917.

Smith and Wesson was fierce about protecting their patents. There were unscrupulous firearms manufacturers in Europe who copied their designs and even forged the Smith and Wesson name on their cheap copies. S&W could not do much about international trade violations, but they could influence what could be imported legally.

Patents expire over time. Trademarks do not. In the 1920s and 1930s inexpensive copies of Smith and Wesson revolvers, mostly manufactured in Spain, were flooding the American firearms market. S&W was able to trademark the color Case Hardening process that they used on their hammers and triggers to prevent cheap copies from being imported.

So, there is a lot more than simple vanity involved in marking firearms. It can be fascinating to study what is revealed by the markings on a firearm.

1911 and 1911A1 are the military designations, and while commonly used to identify them in conversation, the guns that Colt built and sold to the civilian market were not 1911s. They were "Government Models", and so marked.

The one that I have was made in 1918. It does not say Government Model on it anywhere. Instead, on the right side of the slide it says COLT AUTOMATIC CALIBRE 45.

Last edited:

I am not sure when Colt began to use the term "Government Model" for its commercial version of the M1911, The 1912 catalog calls it the Colt Automatic Pistol then in smaller print "Military Model of 1911", Calibre .45.

AFAIK there is no law requiring a manufacturer to mark his product with the patents used. In some products, like computers, the marking would cover the whole case.

But in the 19th and early 20th centuries, many products sold were not patented at all, and folks had the idea that a patent was some kind of "government guarantee" that the item was good. Plus, folks wanted the latest gizmo (like the modern fashion in electronic gadgets) so the later the patent date the better. To further impress the buyer, some companies loaded their products with every patent date they could legitimately use, whether that patent actually applied to that product or not.

Jim

AFAIK there is no law requiring a manufacturer to mark his product with the patents used. In some products, like computers, the marking would cover the whole case.

But in the 19th and early 20th centuries, many products sold were not patented at all, and folks had the idea that a patent was some kind of "government guarantee" that the item was good. Plus, folks wanted the latest gizmo (like the modern fashion in electronic gadgets) so the later the patent date the better. To further impress the buyer, some companies loaded their products with every patent date they could legitimately use, whether that patent actually applied to that product or not.

Jim

bedbugbilly

New member

I'll just answer "ya" . . .

Agree with you but I've learned to ignore it . . . that's one reason I like "vintage" wheel guns but "what is, is".

Think about it . . . you cannot "legislate" common sense . . but thanks to the lawyers (I won't refer to them as shysters or vermin) - the world has come to this. Also . . . I'm a typical "man" - I don't read manuals. BUT . . I do when it comes to firearms. I figure it is part of my being "a responsible gun owner" and it's part of "Learning" a new hand gun - whether it's another SAA and "old hat" - I still do it. I have seen so many posts on forums on "can I shoot "X" in my new "whatever" or my hand gun was really dirty and oily when I got it and it wouldn't cycle properly". Duh! Did you read the manual? "Well . . . no."

I'm of the opinion that you could shackle a new handgun to a bill board and tell the new owner "read your manual" and some would still not do it . . . they "know it all" . . and then are shocked when there is a problem that common sense should tell a person you "can't do" . . . as they say . . "you can't fix stupid". And in the end . . . those folks probably don't even read what's on the barrel nd all the warnings.

But I'm "old" . . been shooting 50 + years and I drank out of a garden hose when I was a kid, walked barefoot through he barnyard and used to have "wars" with "raad apples". Thank goodness I didn't know how "dangerous" all that was. But then in these days, we're dealing with a generation of supposedly "intelligent" people that the hamburger joints have to have a marking on the wrapper that states "place sandwich here". And . . if they screw up . . the typical reply is "I didn't do it . . it's not my fault". And it isn't going to bet any better as the "guvment" has taken on the job of "protecting" us all . . afert all . . . aren't most folks "entitled" now?

We raised dairy cattle years ago. It would not surprise me one bit that someday I'll go bast a pasture with a nice herd of Holsteins in it and everyone will have a sign with an arrow on it pointing to their back side that says . . "CAUTION . . TOXIC WASTE".

O.K. I'll shut up now . . .

Agree with you but I've learned to ignore it . . . that's one reason I like "vintage" wheel guns but "what is, is".

Think about it . . . you cannot "legislate" common sense . . but thanks to the lawyers (I won't refer to them as shysters or vermin) - the world has come to this. Also . . . I'm a typical "man" - I don't read manuals. BUT . . I do when it comes to firearms. I figure it is part of my being "a responsible gun owner" and it's part of "Learning" a new hand gun - whether it's another SAA and "old hat" - I still do it. I have seen so many posts on forums on "can I shoot "X" in my new "whatever" or my hand gun was really dirty and oily when I got it and it wouldn't cycle properly". Duh! Did you read the manual? "Well . . . no."

I'm of the opinion that you could shackle a new handgun to a bill board and tell the new owner "read your manual" and some would still not do it . . . they "know it all" . . and then are shocked when there is a problem that common sense should tell a person you "can't do" . . . as they say . . "you can't fix stupid". And in the end . . . those folks probably don't even read what's on the barrel nd all the warnings.

But I'm "old" . . been shooting 50 + years and I drank out of a garden hose when I was a kid, walked barefoot through he barnyard and used to have "wars" with "raad apples". Thank goodness I didn't know how "dangerous" all that was. But then in these days, we're dealing with a generation of supposedly "intelligent" people that the hamburger joints have to have a marking on the wrapper that states "place sandwich here". And . . if they screw up . . the typical reply is "I didn't do it . . it's not my fault". And it isn't going to bet any better as the "guvment" has taken on the job of "protecting" us all . . afert all . . . aren't most folks "entitled" now?

We raised dairy cattle years ago. It would not surprise me one bit that someday I'll go bast a pasture with a nice herd of Holsteins in it and everyone will have a sign with an arrow on it pointing to their back side that says . . "CAUTION . . TOXIC WASTE".

O.K. I'll shut up now . . .

Driftwood Johnson

New member

I am not sure when Colt began to use the term "Government Model" for its commercial version of the M1911, The 1912 catalog calls it the Colt Automatic Pistol then in smaller print "Military Model of 1911", Calibre .45.

Howdy Again

We are getting a bit far afield for a Revolver Forum, but this 1911 was made in 1918.

A little bit unclear in this photo, but it is marked UNITED STATES PROPERTY on the left side of the frame.