Yikes! Lots of assumptions made and questions to be answered.

Starting at the top: 300 WM has more case capacity variation than any other chambering. It's an artifact of its history, I suppose, but it is the reason QuickLOAD lists the different headstamps as if they were different cartridges, and not just a single listing you adjust.

QuickLOAD's algorithms do an excellent job of predicting pressure once you have adjusted its parameters to match actual velocity performance you get from your rifle. Without making that match, you are limited by the fact its powder database is from measurements of lots of powder the author tested without having a way to know how average those lots were. So the software does OK with giving you a reasonable range, but unless you adjust it to your chronograph readings with your gun's specifics entered in and your case's specifics entered in, you are instead estimating for an ideal test gun with whatever lot of powder Herr Broemel happened to get.

The main reason the loading industry uses pressure guns is that pressure measuring for manufacturing is a statistical QC method designed to produce ammunition safe in guns the maker well never see. Bulk powders purchased by commercial ammunition plants can come with such a wide range of burn rates, a load manual is not useful with them. A pressure gun is the only practical way to determine a safe load, and is the only way to assure conformance with the statistical QC method the SAAMI standard describes. Handloaders buy the more expensive canister grade powders which have more tightly controlled burn rate variation in order to keep load manual data valid. Many handloaders load outside SAAMI pressure standards to match their individual guns by pressure sign observation. The plant manager at Remington has no clue what rifle his customer might be able to take above the standard levels. So, you can see that loading commercially and loading at home have different concerns.

Case capacity has two standard measures:

1. Case Water Capacity (CWC): the case's water capacity left over after seating a bullet.

2. Case Water Overflow Capacity (CWOC): the case's water capacity with water level to the case mouth and with no meniscus.

The former is what people measuring case water to the shoulder are trying for. A better method is to fill a fired case with water and push a bullet in to seating depth and see how much water remains after the excess squirts out past the bullet. CWC in what you want if you are calculating load density or related parameters.

CWOC is what you want for comparing cases to see which one will have the most or the same powder capacity with all bullets. It is also what you enter into QuickLOAD, as the program also has you enter bullet seating depth information and automatically subtracts the space consumed by seating the bullet, which it shows as a result in its Usable Case Capacity output window.

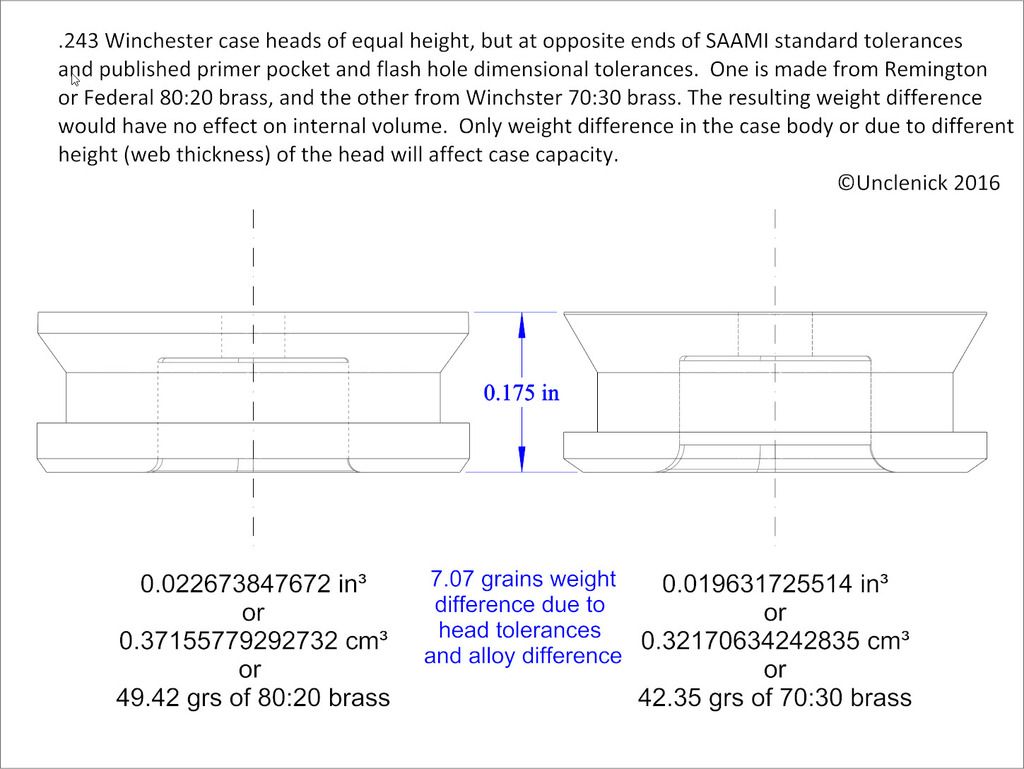

Case weight does not track case capacity perfectly. I have measured a bunch of .308 brass and found difference in weight predicts the difference in capacity to an accuracy of about ±20%. There are two reasons for this limited precision. The smaller one is that

different manufacturers use different brass alloys with different densities:

Code:

[font=courier new]Copper:Zinc Density at 68°F (notes)

60:40 8.39 gm/cc (aka, Muntz Metal)

70:30 8.53 gm/cc (aka, Cartridge Brass or 760 Brass)

80:20 8.67 gm/cc (aka, Low Brass)[/font]

The other factor is that case head diameters, rim thickness and chamfer dimensions, and extractor groove dimensions all have tolerances and different makers don't make them identical. These numbers can all change the weight of the case without affecting its capacity.

How much charge weight to compensate with:

Wm. C. Davis at the NRA worked this out long ago for .30-06, and QuickLOAD confirms that, interestingly enough, it comes quite close to being true for all chamberings, though it varies a little with powder choice. Roughly speaking, for each 1.8 grains of increased water capacity, you increase the powder charge by 1.0 grain. That would be equivalent to a case weight increase of about 15 grains for 760 brass if the head dimensions stayed constant. They don't. Even a single lot of brass is usually the combined output of several different sets of tooling operated in parallel to get the run done quickly.

Headstamps are not good enough to determine brass capacity. Over time, cases vary by lot. Reloadron measured Winchester .308 cases averaging 164 grains. I bought a bulk lot about 2005 that averages 156 grains. The old 1992 Palma match brass was made by Winchester, and I've been told it was about 150 grains. The Norma manual offers up one reason for this. The ammunition industry is incestuous and different members contract with other members to make different components for each other when they are short on capacity or time. Norma says it has made brass for Remington and Federal, among others, and most European brands at times, plus it is the OEM supplier of all Weatherby headstamp cases and loaded ammunition. It also makes ammunition for a number of other smaller brands. If one guy runs out of capacity or has an interruption in production for some reason, he will reach out to someone else to do it for him.

Norma, incidentally, uses 72:28 brass (approximately, and not counting other elements in the alloy).

Per Jeephammer's note, in 2012, ATK put out a call for new brass designs for military small arms cartridges, including 7.62, toward the goal of lightening the loaded ammunition by 10%. So even LC and other military cases can't be counted on to match the past capacities.