What 44 AMP said is true. My reason for posting both all the bullet dimensional variation and the fact shooters are measuring the wrong thing to insure consistent jump, was to point out that controlling actual jump to better than around 0.005" is mostly wishful thinking. It can be done, of course. I made a gauge to measure it years ago, and you can sort your rounds with it and then go back and, using the micrometer adjustment on a seating die, bring the longer bullets down to match the shorter ones. But that begs the question whether or not such control gets you anything. I've not see evidence on paper that it does. I think the reason is that even if you get perfect matching jumps, the variation in ogive length from the bullet base means the annular opening between the bullet and the throat that is responsible for allowing gas bypass will still differ from bullet to bullet.

Dr. Lloyd Brownell suggested back in 1965 that the bypass was what was responsible for throat proximity affecting pressure and he had the plots to prove it (read his study for this and lots of other information). If you look at super slow motion movies of bullets leaving muzzles, you see the bypass gas and some powder particles clear the muzzle first.

I have been left to conclude apparent improvements achieve by tiny incremental changes in bullet seating depth are most often actually random group size changes and not real. Berger seems to have come to the same conclusion empirically.

You are wrong, mostly. Not sure who "theorized" the idea, but HP White labs did a bunch of work decades ago that showed a high power rifle bullet doesn't even begin to move until pressure reaches 10,000-12,000 psi, which is more than a primer can provide. When a primer unseats a bullet, it happens much more slowly. The bullet has too much inertia for the primer pressure to overcome within normal firing event and barrel times. The exceptions are in very small volume cases where the primer pressure actually can get high enough to beat the powder in moving the bullet. The .22 Hornet is famous for having this happen. The result is erratic velocity due to uneven powder ignition. Many pistol cartridges with short powder spaces appear to do the same thing. .45 Auto, for example.

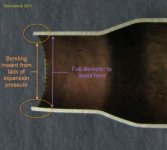

Incidentally, when a high power rifle case fires, the brass starts to expand. The neck does this from the lowest point of contact with the bullet rolling forward. If your chambers aren't too loose in the neck area, you will have noticed that you can't drop a bullet into a fired case. This is because the mouth of the case starts leaking gas before it expands completely. This creates a pressure drop along the narrow space between the bullet and the neck, so there isn't enough pressure to finish expanding the mouth. The result is the mouth curls in very slightly (see sectioned .308 W case image below). The gas leaking through there before the bullet moves forward significantly is the gas bypass I mentioned above.

Dr. Lloyd Brownell suggested back in 1965 that the bypass was what was responsible for throat proximity affecting pressure and he had the plots to prove it (read his study for this and lots of other information). If you look at super slow motion movies of bullets leaving muzzles, you see the bypass gas and some powder particles clear the muzzle first.

I have been left to conclude apparent improvements achieve by tiny incremental changes in bullet seating depth are most often actually random group size changes and not real. Berger seems to have come to the same conclusion empirically.

std7mag said:Now then after the firing pin strike on the primer it has been theorized that there is enough pressure build up to unseat the bullet and shove it into the lands of the barrel before the powder actually ignites to the point of building it's pressure.

Please feel free to correct me if i'm wrong.

You are wrong, mostly. Not sure who "theorized" the idea, but HP White labs did a bunch of work decades ago that showed a high power rifle bullet doesn't even begin to move until pressure reaches 10,000-12,000 psi, which is more than a primer can provide. When a primer unseats a bullet, it happens much more slowly. The bullet has too much inertia for the primer pressure to overcome within normal firing event and barrel times. The exceptions are in very small volume cases where the primer pressure actually can get high enough to beat the powder in moving the bullet. The .22 Hornet is famous for having this happen. The result is erratic velocity due to uneven powder ignition. Many pistol cartridges with short powder spaces appear to do the same thing. .45 Auto, for example.

Incidentally, when a high power rifle case fires, the brass starts to expand. The neck does this from the lowest point of contact with the bullet rolling forward. If your chambers aren't too loose in the neck area, you will have noticed that you can't drop a bullet into a fired case. This is because the mouth of the case starts leaking gas before it expands completely. This creates a pressure drop along the narrow space between the bullet and the neck, so there isn't enough pressure to finish expanding the mouth. The result is the mouth curls in very slightly (see sectioned .308 W case image below). The gas leaking through there before the bullet moves forward significantly is the gas bypass I mentioned above.