MINSH101,

You didn't say what kind of firearm you are loading.

In rifles or other weapons with barrels of around a foot or more, there is a phenomenon in which a powder that is too slow for a bullet can send the light bullet scooting down the tube too early in the pressure build-up. The powder is most vigorously burning first near the flash hole, so powder nearer the front of the case is still just starting to light up when this occurs. As a result of the light bullet opening up the space in front of the case prematurely, the rest of the pressure buildup is mainly behind a plug of remaining powder at the shoulder and mouth of the case and sends that plug down the tube where it catches up to and collides with the base of the bullet as if it was an obstruction. As in the muzzleloading phenomenon called short seating, this can ring or bulge a barrel. Texas Gunsmith Charlie Sisk used to have some photos up on either THR or 24hr Campfire (I've forgotten which, but they are no longer there) of muzzles he'd blown off, IIRC, 338 Win Mags with a particularly bad load of this sort. It would take him ten to a dozen rounds before the muzzle gave way, but they looked like jagged torn metal afterward.

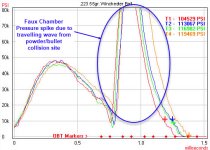

Unfortunately, since the pressure from these events is all local to a point a foot or more down the tube and not at the chamber, the standard SAAMI-type pressure measuring equipment does not show that it's happening. However, the event does send a transverse or traveling wave down the surface of the barrel, so it shows up as a faux chamber pressure reading on strain gauge instruments that are measuring over top of a chamber, even though the actual pressure event was further down the tube. I don't know of any other way to detect it but the strain gauges.

Here's an example of commercial ammunition creating the problem. Obviously, the manufacturer, using standard test equipment, did not see the problem or the load would not be OK'd. This is a strain gauge pressure measurement.

Reproduced with kind permission from Jim Ristow at shootingsoftware.com:

Normal traces from the same source as above:

In a handgun, the above is not normally a concern because the barrel is too short for it to happen in. The bullet getting out too soon just means more unburned and still-burning powder exiting the muzzle after it. As a result, the load is inefficient and the charge weight needed to reach maximum pressure with a slow powder is enough heavier that you wind up with increased muzzle blast, flash, and recoil (from ejecting the extra powder mass). So it's generally a bad choice for low-light shooting or for anyone recoil-sensitive.

As to choosing powder, generally speaking, consistent velocity means consistent ignition and pressure. If you go through data on Hodgdon's site you will note that actual pressures listed are generally below SAAMI spec (though I did find one exception I can't explain). They do not use the SAAMI MAP value the way ammunition manufacturers do, which is as a maximum average pressure (what MAP stands for), but rather use it as a hard pressure limit. The powders with the lowest maximum load pressure are the ones that exhibited the most pressure variation with their highest ten round value reaching the SAAMI MAP. Therefore, as Hodgdon's print manual explains, the loads listed with the highest pressures were the ones that performed most consistently and make a good choice for consistent performance. Note that with some cartridges, Hodgdon's data will mix measurements in CUP and psi. The MAP values for the two systems are different for any given cartridge. You want to compare the highest CUP value to other CUP values and the highest psi value to other psi values, only, if you use this selection criterion.

Another criterion you can employ is to look at velocities and the Hodgdon powder burn rate chart. You will generally find a range of powders with different burn rates that produce close to the same maximum load velocity. Picking the powder with the middle burn rate value from that group will tend to give you the best balance between peak pressure and recoil for those velocities.

Those strategies may be employed for either rifle or handgun cartridges. One other thing that cannot be predicted from published data is which powder will produce the best precision (smallest groups) with your gun. That often takes exploring more than one powder to learn. The reason is that even when velocities match, faster powders produce shorter barrel times than slow powders do, and rifles, in particular, often prefer a specific range of barrel times.