Tipoc

I think you are a little bit confused about the configuration of the different types of hammer blocks Smith and Wesson has used over the years.

When Supica and Nahas mention

'a shoulder on the rebound slide which was forced against a shoulder on the hammer. These shoulders kept the hammer nose off the cartridge in the down position'

this is what they were talking about. This is the same photo I posted earlier of the 1908 vintage M&P. I have added two arrows, pointing to the two shoulders. I call them humps.

There was no separate Hammer Block in revolvers of this vintage. The two opposing humps forced the hammer back so that the firing pin (Nahas and Supica use the term 'Hammer Nose' which is what S&W call a firing pin) was moved back away from the primer of a round under the hammer. You can see in this photo that the hammer is indeed forced back, the third arrow is pointing to a space between the hammer and the frame. I repeat, there was no separate Hammer Block in revolvers of this era. The two humps wedged the hammer back when the trigger was released, removing the firing pin away from a cartridge in the chamber under the hammer. These two humps have always been part of the design of every S&W swing out cylinder revolver since 1905. The actual shape and geometry of them has changed over time, but they are still part of the design, and they are the primary means of preventing a round under the hammer from firing. They have always been, ever since 1905. The various Hammer Block designs that have been incorporated over time are additional safety devices, designed to keep the revolver safe if the 'two humps' failed.

By the way, keep that space between the hammer and the frame in mind, it comes into play later.

I do not have a photo of the first type of Hammer Block that S&W incorporated in the design, Mike Irwin was kind enough to supply one.

You misquoted me calling the photo of the Hammer Block in the side plate as a 1926 era revolver. It is not. 1926 is when S&W started incorporating that type of Hammer Block.

********************

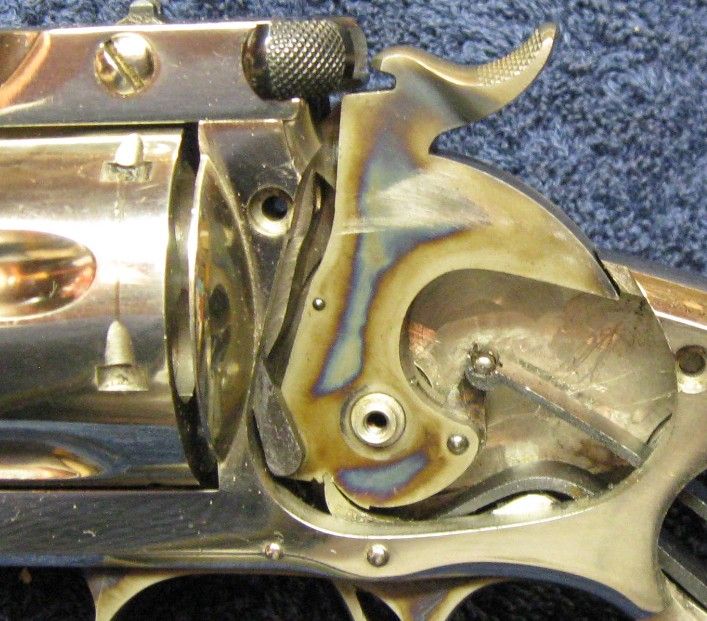

Here is a photo of another revolver with the second type of hammer block in it. This revolver was made in 1939. Don't look for a spring, the entire Hammer Block is a piece of spring steel. It is held in place in its slot at the very bottom where it has been peened to the side plate. You can see the tab on the side of the Hammer Block that rides against the ramp on the hand. This is the type of Hammer Block that failed in the Navy incident involving a Victory Model. You can also see in this photo that the 'two humps' although their shape has changed slightly, are still doing their job of keeping the hammer back.

I am reposting this photo because it shows the hammer block at a slightly different angle. In addition to the tab that rubs against the ramp on the hand, in this view you can see the 'business part' of the Hammer Block that fits into that space between the hammer and the frame.

**************

This is the type of Hammer Block that was designed after the Navy incident in 1944. It is the same type of Hammer block that is still in use in S&W revolvers today. This gun happens to be a Model 17 from 1975, but the Hammer Block is the same as was designed in 1944. It is the same type of Hammer Block that S&W still uses.

Notice that the Hammer Block gets pushed by a pin on the Rebound Slide. Notice too, that the 'two humps' are still doing their job, even though their shape has changed slightly. Notice also that the Hammer Block is in its upper position, sandwiched between the hammer and the frame. The hammer is not actually resting on the Hammer Block, there is a teeny bit of space between the hammer block and the hammer. But if the 'two humps' should fail, the Hammer Block is there to prevent the firing pin from striking a primer.

When the hammer is cocked, or the trigger is pulled, the Rebound Slide is pushed backwards. The slanted configuration of the slot in the Hammer Block causes the pin to pull the Hammer Block down diagonally in its slot, clearing the hammer so the gun can fire.

This is how the modern Hammer Block rides in its slot in the Side Plate.

Just for fun, here is a photo of the lockwork of a big N frame revolver, a 44 Hand Ejector 4th Model (Model of 1950 Target). This gun shipped in 1955. Even though the parts are bigger, they function the same way.

I hope this helps make the function of the various Hammer Blocks (and the lack of one) clear.