Howdy

Let's look at a little bit of firearm mechanical history. It was a well known fact that in the 19th Century, most of the old, large frame, single action revolvers were not safe to carry with a live round under the hammer. Here is a photo of the main lockwork parts or a Colt Single Action Army; hammer, trigger, bolt, and hand. The two arrows are pointing to the weakest portions of the hammer and trigger. The upper tip of the trigger; the sear, is very thin, and not particularly strong. The hammer has three 'cocking notches'. The upper arrow is pointing to the so called 'safety cock' notch. The next one is the half cock notch, and the lowest notch is the full cock notch. Notice how the 'safety cock' notch and the half cock notch have an over hanging lip. This is to trap the sear, so the trigger cannot be pulled when the sear is in either of those two positions. At least that is the idea.

With the hammer at the 'safety cock' position, the hammer is back around 1/8" or so and the firing pin cannot contact a primer. The reality is it did not take much of a blow to either shear off the sear, or shear off the over hanging lip of the 'safety cock'. Dropping a Colt (or most other 19th Century Single Action revolvers) from waist height so that it landed on the hammer spur was almost guaranteed to shear off something so that the firing pin would hit the primer under it and the revolver would discharge. The gun did not even have to be dropped. When a horse is saddled, one of the stirrups is always folded up over the top of the saddle so the saddle could be strapped under the horse's belly. If the stirrup were then allowed to fall onto the hammer of a holstered gun, there was an excellent chance it would discharge. As a matter of fact, with the sear in either the 'safety cock' or the half cock notch, a really strong tug on the trigger could shear off the sear, rendering the revolver unsafe.

All this is why Bill Ruger changed the design of his Single Action revolvers in the 1970s revolvers to include a transfer bar. But that is a different story.

By the way, this is all about revolvers that have the hammer down, not cocked. If somebody dropped one of these revolvers while it was cocked, there is an excellent chance the sear would be jarred out of the full cock notch, discharging the firearm. But this technology is about preventing an

uncocked revolver from firing, not a cocked revolver.

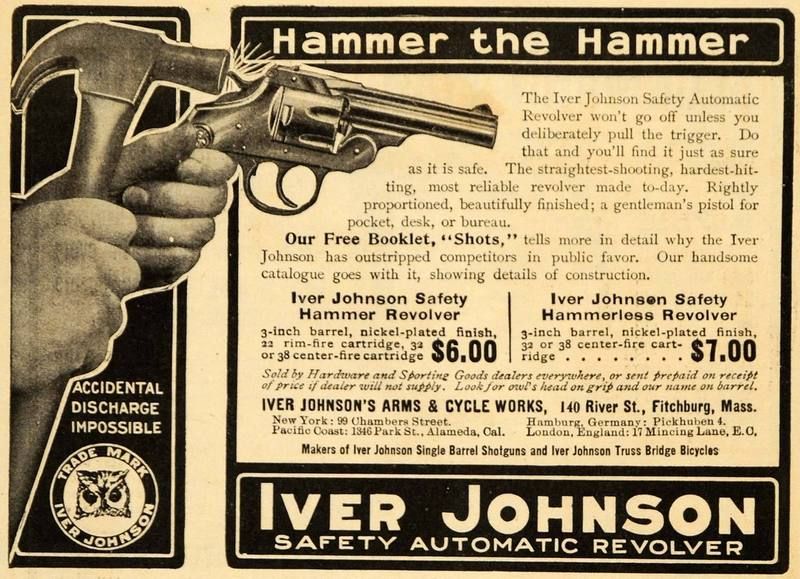

In 1896 Iver Johnson was granted a patent for what we know today as a Transfer Bar. The revolver would not fire unless the Transfer Bar was in position between the hammer and the frame mounted firing pin. Just like a modern Ruger, the Transfer Bar would only be in position to transfer the blow of the hammer to the firing pin when the trigger was pulled all the way back.

They followed this up with a well publicized marketing campaign they called 'Hammer the Hammer'.

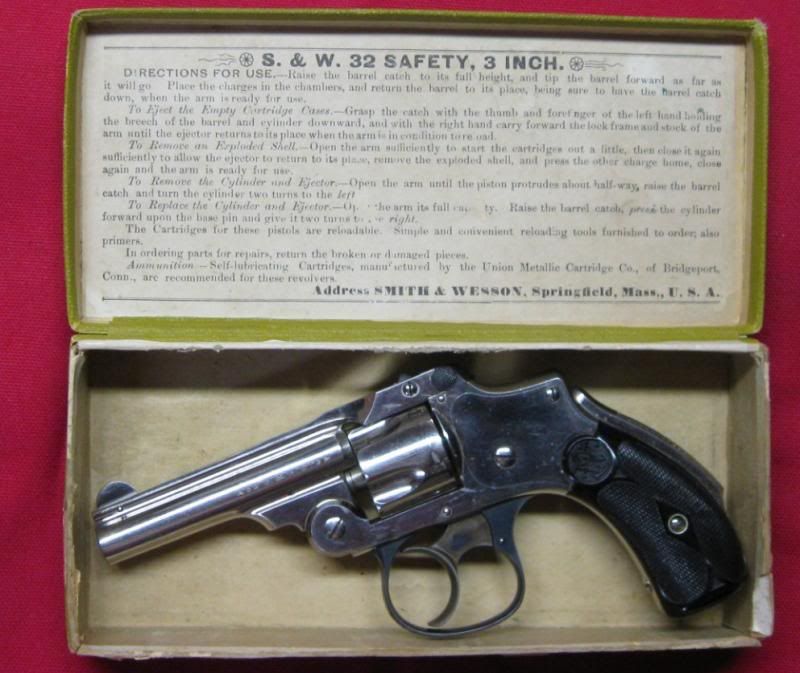

Smith and Wesson chose a different design route. Their 'Safety Hammerless revolvers had a grip safety. You can see it at the rear of the grip. This was a double action only revolver, the hammer was completely internal. Just like with a Model 1911, if the grip safety was not squeezed, the firearm would not discharge. That is why these revolvers were sometimes called Lemonsqueezers.

When Smith & Wesson built their first 38 caliber, side swing revolver; the 38 Military and Police Model of 1899, it did not have the Rebound Slide, neither did the Model of 1902. They relied on a spring loaded lever to ear the hammer back so the firing pin would not contact a primer.

The Rebound Slide first appeared in the model of 1905. This Model of 1905 shipped in 1908. There is no hammer block of any kind. The spring inside the Rebound Slide has pushed the slide and the trigger forward, and the hump on the top of the Rebound Slide has wedged the hammer back slightly, withdrawing the firing pin from any round under the hammer. I hear folks who are not familiar with the mechanics of these revolvers claiming how they are not safe to carry fully loaded with six rounds and should only be loaded with five rounds, with an empty chamber under the hammer. Hogwash! Just look at the mechanics. These parts are much more robust than the flimsy parts inside the old Colt. Smith & Wesson put a lot of thought into these guns, and they were designed to be fully loaded with six rounds. Yes, it is possible for a really strong blow to the hammer to shear off the toe of the hammer at its thinnest point, or to even break the hammer pivot stud, but it would probably take a lot more than just dropping the gun from waist height. One of these days I mean to do a little bit of testing of that theory.

Despite all that, as early as 1915 S&W decided to install a hammer block in the Model of 1905. The side plate was slotted, for the hammer block, which was operated by a plunger pushed back by the hand.

A new type of hammer block was designed and installed in all models beginning in 1926. Here are photos of the second style of hammer block. Notice the 'ramp' built onto the hand.

Here is the hammer block. It is a piece of spring steel pinned into the side plate. When the hand rises, the ramp contacts the tab on the hammer block, pushing it out of the way so the revolver can fire.

*****************

Now let's talk about that incident where the sailor was killed when a Victory Model fell to the deck of a warship. First off, this was a very rare occurrence. Not that that is any consolation to the dead man, but old Colts firing when dropped was a much more common occurrence than a 38 M&P discharging when dropped. Second, it was not 'his revolver' that fell. The revolver in question may have fallen much farther, it may have fallen off the superstructure of the warship. All these hammer blocks, including the ones currently installed in S&W revolvers, are a redundant safety. The hump on the top of the Rebound Slide has always been the primary safety device inside every S&W revolver built since 1905. What happened in this case was a cascade of bad luck. The gun fell a great distance, and the hammer block was clogged with Cosmoline, so it did not spring back to the 'safe' position.

In 1944, after the Navy investigated the accident, the current style of sliding hammer block was designed. Approximately 40,000 revolvers were shipped back to the factory to be retrofitted with the new style of hammer block. This was wartime, and the government insisted that if S&W wanted to keep their contract to supply revolvers, they better fix it fast. I believe the engineers were called in and had the new design completed over a weekend. The revolvers that were retrofitted had a small 's' stamped near the rear sideplate screw, and a large 'S' stamped on the butt alongside the Serial Number. That is the same type of sliding hammer block that is still installed in all S&W revolvers today. It is operated by a pin on the Rebound Slide, and has been said it is more positive than the older style hammer block.

But it is still a redundant safety. The rebound slide still wedges the hammer back, and it would take a mighty blow to shear the hammer or the hammer pivot stud, so that the hammer block could actually come into play and do what it was designed to do.

I do agree there is no point to removing the hammer block. It does float, one cannot tell if it is in there or not just by the feel of the trigger. But if you peek under the hammer at just the right angle you will see it is there.