Kenya: Jumbo Wars Come to Country

The East African (Nairobi)

29 June 2008

Posted to the web 30 June 2008

John Mbaria

Nairobi

AS THE LARGEST LAND-Based animal, the elephant has the ability to excite strong emotions - emotions that now pit different African countries against each other over whether the beast has more value alive or dead.

The jumbo dispute was once again played out recently in Mombasa's Whitesands Hotel, where representatives of 19 African countries met to cement their unity and sharpen their campaign against the resumption of the ivory trade.

Meeting under the auspices of the African Elephant Coalition, the group called upon the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (Cites) not to allow China to be a partner in limited ivory trade allowed by the UN body two years ago in The Hague.

During the no-holds-barred event, Kenya, as usual, dug its heels in deep. It was obvious that the country, together with Mali, is the leader of the anti-trade pack.

Uganda was conspicuously absent and so was Tanzania. But unlike the latter, which allows sport hunting and has always voted with those calling for the resumption of the ivory trade, Uganda's voice (it emerged) has become somewhat confused.

It was revealed that officials in Uganda Wildlife Ministry advocate a resumption of the ivory trade, while the Uganda Wildlife Authority supports Kenya in calling for a total ban.

Interestingly, the group of African countries calling for a total ban also happen to be among the poorest in the world. Besides Mali, Sierra Leone, the Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, there are Senegal, Southern Sudan and Ghana, countries that do not have the wherewithal to effectively conserve their wildlife. Their human populations are not in any better shape.

Meanwhile, South Africa and Botswana - who lead the pro-trade group in Africa - not only have high gross domestic products, but are able to keep their wildlife away from unlicensed killers; they are also effective in strategising during international elephant diplomatic meetings.

THIS WAS EVIDENT DURING the last Cites meeting at The Hague, when they scored yet another victory after the UN body allowed them to sell 107 tonnes of ivory to Japan.

To the countries down south, the African Elephant Coalition's argument that lifting the ban on the ivory trade would open the floodgates to illegal trade and poaching does not wash. They have constantly argued that - as effective managers of their resources - they should not be penalized for the inability of Kenya and its other anti-trade colleagues to secure their elephant herds from the poachers' guns and snares.

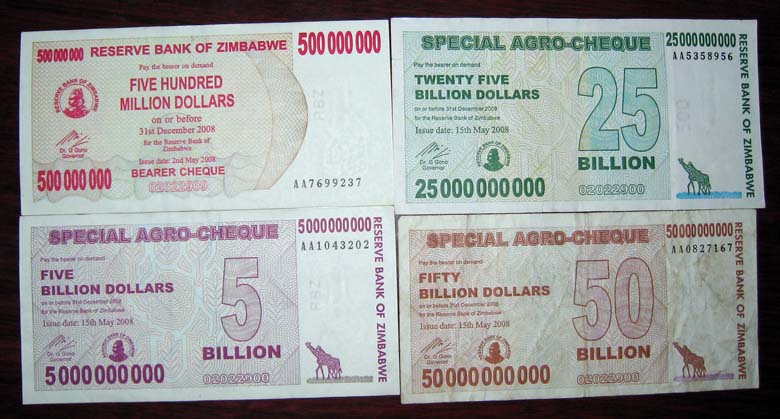

So, what is it that Kenya and fellow anti-ivory trade states know that informs their anti-ivory trade stance and that seems to have escaped South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe - and all the other countries outside Africa that see more value in dead elephants?

Patrick Omondi of Kenya Wildlife Service, who is considered the foremost elephant expert in Africa, presented facts and figures that even Southern African countries ought to be concerned about.

According to Omondi, the vast areas Africa has - throughout history - devoted to elephants to feed, breed and play, are largely gone.

Omondi told the gathering in Mombasa that the elephant can be found in 37 so-called range states. Their habitats there range from the vast grassland-dominated savannah (in East and Southern Africa) to such significant tropical forests as those found in the Congo Basin and parts of West Africa.

"Of the 2.6 million square kilometres now available for elephants on the continent, only 31 per cent are protected areas." He said such protected areas in Southern Africa constitute 39 per cent of the elephant range, 22 per cent in East Africa and 39 per cent in West Africa. Elephants inhabiting protected areas are relatively safer from illegal poaching.

FURTHER, IT IS APPARENT that Southern Africa has the largest amount of open land for elephant conservation and also the biggest known population of elephants on the continent.

Quoting data from the World Conservation Union (IUCN), Omondi said elephant numbers in different parts of the continent reflect the amount of land open for their conservation.

Southern Africa leads with 297,715, East Africa follows with 137,485, while Central Africa has 10,383 and West Africa has a small population of 7,487.

This means there are 472,269 elephants remaining in Africa today.

"What we are looking at here is a situation of too many elephants in some regions and too few in other regions," said Omondi.

He added that the issue is not merely about the impact that allowing international trade would have on the numbers, but also about how to manage elephants that criss-cross international boundaries - particularly when the relevant countries pursue conflicting conservation policies such as Kenya and Tanzania.

There are also other issues such as getting the world to appreciate the threat posed by human-elephant conflict in different African countries. "Surely, for a country like Senegal that has less than 10 elephants, it is important to know the story behind the low numbers," he said.

"We need an environment in which each country can be given a chance to explain the status of its elephant herds and why such a country has decided to take one or the other position on the international trade in ivory," he added.

During the Mombasa meeting, the delegates talked about systematic depletion of habitats and widespread poaching - particularly in the Central African Republic and Congo - while others talked about how elephant-human competition for available space and resources has affected numbers because, almost always, the beast ends up being the loser.

But it was Maj-Gen Alfred Akwoch, Undersecretary for the Environment and Tourism Ministry of Southern Sudan, who carried the day.

Maj-Gen Akwoch regretted that many international conferences on endangered wildlife happened before his government had signed the Comprehensive Peace Agreement with Khartoum government. He said that Southern Sudan has seven ecological regions that support localised elephant populations. "Although such ecological zones do not extend to the North, ivory had always been illegally acquired from Southern Sudan. It is obvious that as we fought the war, our adversaries were busy killing elephants."

And just like humans, some of the elephants in Southern Sudan became refugees in northern Uganda, he said.

Ironically, the long-running war in Southern Sudan seems to have helped to save elephants and other wildlife from total annihilation.

For instance, a report released recently by Unep shows that the population of kob (white-eared antelopes) has been growing steadily from the last count in the 1970s and now stands at 1.2 million.

Unep noted that the same phenomenon was unobserved anywhere else in Africa. But Maj-Gen Akwoch had an explanation for it.

He says that during the war, the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) issued a decree prohibiting its fighters from killing wildlife.

"One of our main interests in fighting the war was to save our resources from exploitation by the North, so we had asked everyone in SPLA to always carry a booklet that detailed a law barring them from ever killing wild animals. Indeed, when our fighters got hungry, a meeting had to be held to deliberate on what animal to kill and how," he said.

Although Southern Sudan is handicapped by lack of resources as far as managing its wildlife and other natural resources is concerned, it has now teamed up with Kenya and other states in the coalition to say "No" to the ivory trade.

The government in Juba is receiving considerable support and expertise from Kenya.

Already, it has hired Perez Olindo, a former director of the Wildlife Department in Kenya, as a consultant, and has formally asked Kenya to help in conducting a census of elephants and other wild animals.

But it seems that Southern Sudan still has a war to fight before it can actualise this dream. Its government is yet to be recognised as a voting member by Cites.

Officially, Sudan is recognised as one party at Cites meetings.

But the government of Southern Sudan is all but an independent government. Since the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, Juba has sought more visibility and international recognition pending the 2011 referendum that is expected to make it Africa's 54th state.

BUT EVEN BEFORE THEN, THE Southerners want a bigger say in the management of their elephant herds and other natural resources and Kenya seems to be the natural partner to provide the necessary expertise.

Other organisations like the International Fund for Animal Welfare and the Born Free Foundation have also come calling with much-needed dollar to secure Southern Sudan's five national parks and 13 game reserves.

For Central African countries, the worry is that their diminishing elephant populations will disappear if the trade is allowed.

The raging conflicts in Congo, Chad and the Central African Republic have given poachers free rein to reduce the already small elephant numbers in the region. Central Africa is thus fearful that allowing China to partner in the limited ivory trade will worsen the poaching that is currently going on there.

It was evident from the meeting that China's renewed quest to be allowed to buy part of the 107 tonnes of ivory that countries in Southern Africa were allowed to sell to Japan, has not gone down well with countries forming the African Elephant Coalition.

Delegates to the Mombasa meeting felt that Cites ought to respect an earlier decision that barred China from buying the relevant ivory.

It seems that the fear is that China, unlike Japan, has not come up with an effective way of ensuring that illegally-acquired ivory is not traded within its boundaries.

"One of the conditions given to Botswana, South Africa and Namibia for the one-off sale in 2002 was that the buyer needed to prove that they had the capacity to effectively prevent the proliferation of the illegal ivory trade," said Omondi.

His sentiments were echoed by Perez Olindo who said that China does not qualify to be a partner in the trade because "it has not put in place a legal mechanism to control all the ivory entering its territory, neither has it been able to prevent illegal ivory from being traded." It was revealed that illegal ivory trading has been taking place in the Chinese city of Shanghai.

"It is strange that even after the Cites secretariat identified illegal ivory trading in China, it nevertheless went ahead to put China's renewed request on the table," said Omondi.

But as the accusations against China flew from one corner of the hall to the other, the enigmatic dragon was nowhere to defend itself.

Nevertheless, the African elephant Coalition was asked to mount a formidable opposition to China's request. Most of the delegates went along with this position as one after the other expressed solidarity with Kenya.

On their part, Togo, Cameroon, Congo Brazzaville and Sierra Leone said that even before China raised the request, they had been losing their small elephant populations to poachers largely because of lack of manpower on the ground.

Some felt that because their elephant numbers are so small, countries with bigger populations should consider donating some elephants to boost their populations.

Delegates suggested the use of DNA profiling of ivory in the market as an effective method of monitoring where the ivory came from in the first place.

Others suggested that to reduce pressure on habitat by elephants in South Africa and Botswana, the two countries should consider allowing some of the elephants into Mozambique, which is part of the elephant range in Southern Africa.