Winchester was contracted to make the cases for the 1992 Palma Match ammunition. That year the U.S. hosted and the host country was required to supply either 7.62 NATO or .308 Winchester headstamp ammunition with 155 grain bullet upper weight limit at that time (Internet rumors as to their differences notwithstanding, the same chambers were used for both in Palma rifles). Mid Tompkins had got Sierra to create their 155 Grain MatchKing for the event, and got Winchester to make a 150 grain case because the extra capacity maximized the amount of powder that could be used which got every last foot per second of velocity for the 1000 yard event, for which they were on the tippy edge of going transonic. The difference was about 50 fps additional velocity from a 32" Palma barrel, IIRC. Winchester used minimum brass thickness and their semi-balloon head case configuration for that design. Today they still have the semi-balloon head in their .308 Win cases, but the brass is a little thicker, so they aren't quite that light and some lots seem to go up into the 160's, so there's some variability coming from somewhere.

The last batch of bulk Winchester .308 Win brass I bought weighed 156 grains ±3 grains. At the other extreme, I've had PMP brass at 185 grains, which is as much as the last Winchester 30-06 bulk brass I bought weighed. If that weight difference were entirely forward of the case head and affecting case capacity and if the brass alloy was the same density, then the Winchester cases, being 29 grains lighter, would have 3.4 grains less water capacity under the bullet, and would need about 2 grains more of most powders to reach the same peak pressure, .

William C. Davis, Jr. did that experiment with 30-06 back in the 1960's. Some rather heavier cases were available back then. Lake City averaged about 195 grains, but Peters had one that was about 215 grains. He concluded you needed about 1 grain of IMR powders for every 16 grains difference in case capacity. I find it's usually more like 14 grains brass weight for each additional grain of powder, and that number holds up fairly well for 30-06, .308 Win, and even in .223 Rem. But different powders have different curves and that's not really going to be a fixed value for all; just an approximate expectation.

In QuickLOAD a .308 Win case, using the same charge in both a 185 grain PMP case and a 156 grain Winchester case results in 12% lower peak pressure and 2.6% less velocity from a 24" barrel. If you've done any pressure and velocity testing of ammunition, you'll know it is not unusual for the cartridges made up with just one load and consistent headstamps to have that kind of peak pressure variation and, in a poorly filled case, in particular, that kind of velocity variation depending on whether the powder is over the flash hole up forward up against the bullet. Add to this the difference in barrel time and the resulting difference in muzzle positions and you can see how some shooters would see no difference on targets at normal ranges. At 1000 yards, though, the difference could be substantial, particularly if the slower bullet goes transonic while the other remains supersonic all the way to the target.

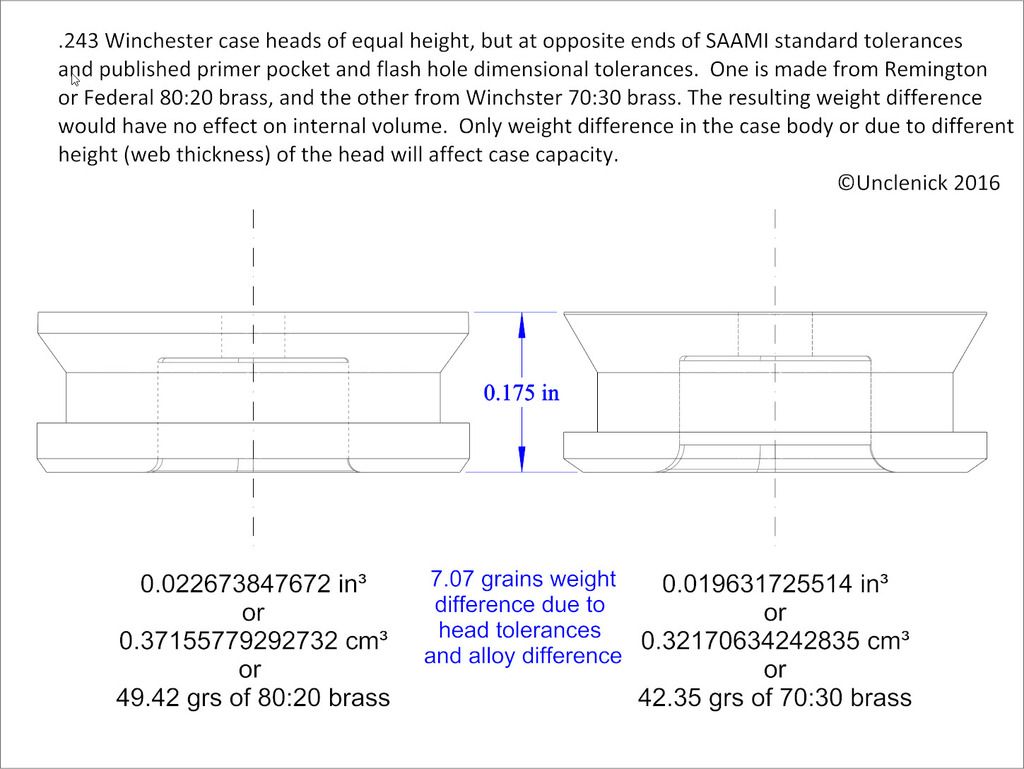

But before you run out and start weighing your cases for a broad answer, there are two other factors. One is that case dimensions have tolerances, including at the head. If you make the head wider or give it a shallower extractor groove angle, but don't change the head thickness from outside to the inside bottom of the case, you have added weight without changing capacity. A .243 Win case head is shown below as an example using the limits of the SAAMI standard dimensions.

In addition to that, not all cases are the same alloy. Federal and Remington use 80:20 brass and Winchester and Lake City use 70:30 brass, and, in the past during wartime, in particular, even 60:40 brass has been used to save copper. These alloys don't have identical density, though the difference means much less to case weight than the physical dimensions do.

From Matweb:

Copper:Zinc / Density at 68°F / Notes

60:40 / 8.39 gm/cc / (aka, Muntz Metal)

70:30 / 8.53 gm/cc / (aka, Cartridge Brass)

80:20 / 8.67 gm/cc / (aka, Low Brass)

100:0 / 8.93 gm/cc / (aka, Copper)

HiBC,

We all love our siblings, don't we? But, alas, your brother steered you incorrectly on case volume for use in QuickLOAD. With

permission from NECO's Ed Dillon, below is a screen shot from QuickLOAD's bullet and brass and gun input section. You will see it is case water overflow capacity that is the entered value (top circled value). The bullet database contains the bullet dimensions, so the software figures out the volume of the inserted bullet (middle circled value) and automatically subtracts it from the case water overflow capacity to give you case water capacity (bottom circled value). The latter two circles are grayed out, meaning you cannot enter them directly. Only the case water overflow capacity is available to alter. The way your brother had you figure out a number he will be figuring your loads with less powder space than you actually have, getting higher pressures at smaller powder charges.

Here is what typical bullet data in the program looks like, and that it uses to work out how much volume a bullet base subtracts from the internal case capacity:

I have an Excel file for helping walk you through getting the right value.

Here is a download link for it that will be good for 30 days.