You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Primers

- Thread starter Tlewis81

- Start date

NoSecondBest

New member

Primers can change the tightness of a particular load in a rifle. It won't be an extreme difference, but can be one that is repeatable and measurable. I had one .243 load that simply had to have CCI primers to get the most out of it. Any change and the groups would open several tenths of an inch.

Anyone ever see a difference in accuracy with a different brand of primers in rifles? Say federal to winchester or remington?

These are some good examples of primer flash making it apparent that primers vary quite a bit manufacturer to manufacturer and eve within a manufacturer.

Another interesting read can be seen here where a home brew device was used to measure primer power (brisance) on a range of primers.

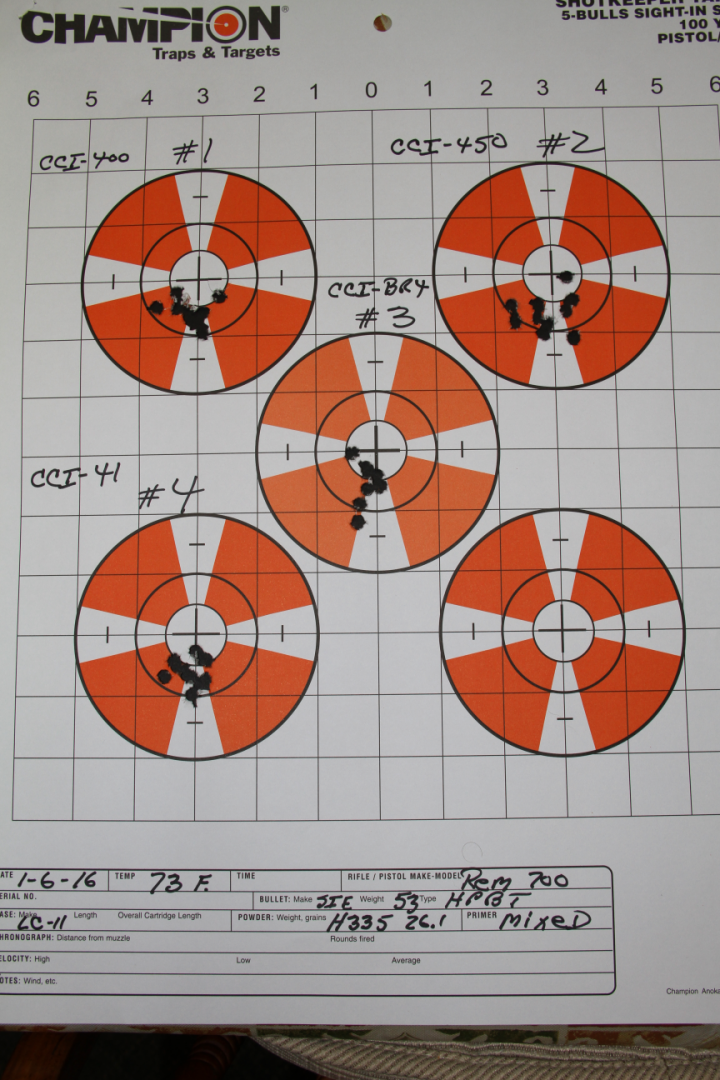

A few months ago I tried a small test using four different CCI primers.

Cases: LC-11

Caliber: 5.56 NATO (.223 Remington)

Powder: H-335 26.1 gn.

Bullet: Sierra 53 gn. HP Match

Rifle was a Remington 700 1:12 twist 26" barrel.

Average Velocities:

CCI 400 was 3372 FPS

CCI 450 was 3366 FPS

CCI BR4 was 3384 FPS

CCI #41 was 3418 FPS

All groups were 10 shots fired at 100 yards. The groups could have been better as I was more focused on the velocities bu tit is apparent the CCI #41 yielded the best group.

Ron

NoSecondBest

New member

Pretty much mirrors my results in changing primers. I wouldn't stay home from hunting if I didn't have the ones I wanted to use, but for prairie dogs and such you might miss one once in a great while. Nice post Ron.

I had been loading for some time before I tested primers.

Then I found that a lot of my issues would be with what is available.

After I find the powder I like and test the load for the tightest group. That is when I will test for the best primer. I will always find a clear favorite with rifles.

Times change I will have a good batch of primers then after a number of years I will find that maybe the manufacturers made a change and I will find another primer works better.

Primers do matter

Then I found that a lot of my issues would be with what is available.

After I find the powder I like and test the load for the tightest group. That is when I will test for the best primer. I will always find a clear favorite with rifles.

Times change I will have a good batch of primers then after a number of years I will find that maybe the manufacturers made a change and I will find another primer works better.

Primers do matter

It is very subtle, smaller than the effects caused by powder charges, bullets, case types.

The best article I have read about the effects of varying components was the Dec 2008 "Developing the Most Accurate 308 Winchester Load" by Gary Sciuchetti. https://www.riflemagazine.com/magazine/PDF/hl257partial.pdf His data indicated that different primer brands and types can change group size up to 0.313" (at 100 yards). Changing powder quantity changed groups 0.75".

Generally, the target shooters I know go out and experiment and stick with the combination that provides the best accuracy. Primers however, like powder lots, vary lot to lot. So stating that one brand is the best is an over reach. The next lot of that brand's primers will be different. Many target shooters I know use CCI Benchrest, but then, back in the day, Federal Match was the preferred primer. From what I have read, CCI Benchrest have tightened quality control requirements, but, the popularity may also be due to the fact that if a manufacturer stamps "sniper", or "match" on a cow patty, shooters will break their wrists reaching for their wallets. That is, shooter perceptions are highly influenced by labels and advertising.

A bud of mine used to go to ammunition plants. Workers were rewarded for making the most consistent batch of primers, but, who won the primer mix cash award varied from batch to batch. Neither the manufacturer, nor the workers, understood why this is so.

The best article I have read about the effects of varying components was the Dec 2008 "Developing the Most Accurate 308 Winchester Load" by Gary Sciuchetti. https://www.riflemagazine.com/magazine/PDF/hl257partial.pdf His data indicated that different primer brands and types can change group size up to 0.313" (at 100 yards). Changing powder quantity changed groups 0.75".

Generally, the target shooters I know go out and experiment and stick with the combination that provides the best accuracy. Primers however, like powder lots, vary lot to lot. So stating that one brand is the best is an over reach. The next lot of that brand's primers will be different. Many target shooters I know use CCI Benchrest, but then, back in the day, Federal Match was the preferred primer. From what I have read, CCI Benchrest have tightened quality control requirements, but, the popularity may also be due to the fact that if a manufacturer stamps "sniper", or "match" on a cow patty, shooters will break their wrists reaching for their wallets. That is, shooter perceptions are highly influenced by labels and advertising.

A bud of mine used to go to ammunition plants. Workers were rewarded for making the most consistent batch of primers, but, who won the primer mix cash award varied from batch to batch. Neither the manufacturer, nor the workers, understood why this is so.

NoSecondBest

New member

Over the last couple of years during the "shortage", a lot of shooters tried Tula primers and guess what? They are really good primers. They are the same as the Wolf primers and are of Russian origin. I've been using them for over a year now and I don't think I'll ever go back to anything else.

The brisance is important but consistency is even more important. Some cases will favor primers with less brisance and some more. The size of the case or the powder could be the reason. That is the reason I will continue to test loads with different primers.

One example I can think of is. My 222 Rem. shoots best at this time with Rem. 7 1/2. At one time it was CCI. I rarely have seen Federal primers on the shelf so I can't very well test them.

I loaded a 22 Hornet and found the 7 1/2 that worked so well with the 222 didn't group well. Although The Rem. # 6 1/2 was found to make the difference.

One example I can think of is. My 222 Rem. shoots best at this time with Rem. 7 1/2. At one time it was CCI. I rarely have seen Federal primers on the shelf so I can't very well test them.

I loaded a 22 Hornet and found the 7 1/2 that worked so well with the 222 didn't group well. Although The Rem. # 6 1/2 was found to make the difference.

I suppose that a person could run thousands of rounds through a barrel before finding that perfect combination, and since every brand of primer will have at least nominal effect on a cartridges ignition, maybe testing primers would be or of the final stages of tweaking, looking for just a few more hundredths of an inch.

Warren page wrote about shooting in matches, and running maybe 100 rounds in accuracy testing for every round fired in competition. The guy was never satisfied, and he would have loved the new equipment we have.

Warren page wrote about shooting in matches, and running maybe 100 rounds in accuracy testing for every round fired in competition. The guy was never satisfied, and he would have loved the new equipment we have.

Nice example Ron. I have been a believer that primers can make a difference. its nice to see your proof.

While I do not dis-agree, statistically to be worth assessing we need to see more groups of each fired.

I would like to see 5 groups of each fired, then assess.

While I do not dis-agree, statistically to be worth assessing we need to see more groups of each fired.

I would like to see 5 groups of each fired, then assess.

I agree. When I did that little test using 10 round groups I was more concerned with velocity and also, for that reason only focused on CCI primers. I actually loaded 25 each of the four primers used for a total of 100 rounds and still have 15 of each remaining.

The testing should be expanded to include large rifle also like .308 Winchester as well as a variety of primers, not just CCI flavors.

All of that said the ten round groups I fired amount to a good start.

Ron

Exactly. For most of us loading range ammo for offhand shooting, it won't be enough to notice or matter, but when you are trying to squeeze the tightest group possible, it is a good, final, fine tuning measure. it's not where you go when you can't keep you "group" on the paper.

A person could never accomplish a really definitive answer to these things, I don't think. Many Hundreds of rounds with a couple of five shot groups, using a small range of charges for only a small selection of powders, even if you held it to one bullet, one brass, and only two charge weights, firing the whole sequence several times on several occasions, even that may be a pointless exercise, until a half dozen cartridges were tested, with at least that many rifles, and then, you'd have to start charting all of those rounds for comparison.

For example, take 30-06. three five shot groups, taken three days apart, testing top and bottom charges only, then testing three brands of primers, that amounts to 135 rounds just for the bare, absolute minimum statistical checkpoints to test for primer efficiency, and still, that's only for a single powder. You can't generalize with only one powder, you would have to test at least three, chosen from the top, middle, and low range of powder speed. Nearly half a thousand rounds, just to get the absolute, rock bottom statistical information to offer any sort of accurate results.

Of course, every round would have to be once fired brass from the same lot, how could a test be accurate if every batch fired had brass that was modified by the previous round of testing?

Then a thorough testing would require the entire sequence to be repeated with probably three different calibers of varying types, such as 243, 270, and maybe 30-30, a group of various charge capacities and various bullet weights on configurations.

Even a very casual test protocol would have to take place in a ballistics laboratory with a big budget. Well over 1,000 rounds, fired with new brass, hand loaded and fired, lord, that's too darned much time for any one person to accomplish in a reasonable time, and more than most people would want to spend.

And as I said, that's the bare minimum. Three five shot groups, three brands of primers, three ranges of powder in three very different cartridges.

I have a feeling I've messed up somewhere on that math. I think that it's probably a lot more than the thousand rounds that I suggested.

For example, take 30-06. three five shot groups, taken three days apart, testing top and bottom charges only, then testing three brands of primers, that amounts to 135 rounds just for the bare, absolute minimum statistical checkpoints to test for primer efficiency, and still, that's only for a single powder. You can't generalize with only one powder, you would have to test at least three, chosen from the top, middle, and low range of powder speed. Nearly half a thousand rounds, just to get the absolute, rock bottom statistical information to offer any sort of accurate results.

Of course, every round would have to be once fired brass from the same lot, how could a test be accurate if every batch fired had brass that was modified by the previous round of testing?

Then a thorough testing would require the entire sequence to be repeated with probably three different calibers of varying types, such as 243, 270, and maybe 30-30, a group of various charge capacities and various bullet weights on configurations.

Even a very casual test protocol would have to take place in a ballistics laboratory with a big budget. Well over 1,000 rounds, fired with new brass, hand loaded and fired, lord, that's too darned much time for any one person to accomplish in a reasonable time, and more than most people would want to spend.

And as I said, that's the bare minimum. Three five shot groups, three brands of primers, three ranges of powder in three very different cartridges.

I have a feeling I've messed up somewhere on that math. I think that it's probably a lot more than the thousand rounds that I suggested.

Reloader270

New member

The test by Reloadron is an example of a fixed powder load with different primers. Due to different burn patterns of primers, this is not proof that one primer is more accurate than the other. The reason is that you need to fine tune the load to the primer. Like adjusting the carburetor of a 1970 Chevy.

Sure Shot Mc Gee

New member

Don't know if there is a difference?"

I only use Federal brand. Hot and dependable ignitions. That's all I need. "Each time & every time."

I only use Federal brand. Hot and dependable ignitions. That's all I need. "Each time & every time."

CAUTION: The following post includes loading data beyond or not covered by currently published maximums for this cartridge. USE AT YOUR OWN RISK. Neither the writer, The Firing Line, nor the staff of TFL assume any liability for any damage or injury resulting from use of this information.

Several things can cause confusion on this topic. First, brissance does not mean primer power in the sense most people or the pendulum test discern it. That is, it doesn't determine the size or total energy of the flame or the quantity of hot gas or sparks produced, though it does affect its duration.

Brissance is tested by setting off a fixed quantity of explosive in sand that has been graded in specific mesh sifters to have no fine particles left. After the explosion, the sand is re-sifted using the finest grading mesh previously employed to see how much new fine sand broken down by the explosion comes through. So brissance is the sand shattering quality of the explosive. It is a measure of the suddenness of the explosion, as a more sudden explosion concentrates more energy in its wave front, and the higher that energy density the more abruptly it impacts solid matter and the more shattering ability it has.

One effect of changing primers is to change peak pressure. In 2006 in Handloader Magazine, Charles Petty ran the same 223 load (24 grains of RL 10X and 55 grain V-max; one grain over Alliant's listed maximum) with a range of primers and got muzzle velocity change of about 4.8% (3150 fps mean to 3300 fps mean velocity). In the latter case the powder was being lit up faster, giving it a higher equivalent burn rate, so it peaked sooner and higher, raising bullet early acceleration. Since velocity goes up directly with powder charge at typical rifle pressures, it was equivalent to the velocity effect of increasing the powder charge about 4.8%. However, to reach the same velocity from the smaller quantity of powder burning faster, the pressure peak goes up a bit more. In this case, the rough equivalent of a 5.3% increase in 10X powder charge, which produces about an 18.5% increase in peak pressure (from QuickLOAD model).

When you change how early in a barrel the acceleration peaks, even though the powder charge and therefore the muzzle pressure are close to the same, the bullet runs down most of the barrel with a faster head start. This means the barrel time is shortened. Load tuning typically produces sweet spots when the barrel time of a bullet and the pressure and recoil-induced whip of the muzzle are synchronized at a slow changing phase in the swing. So when you alter barrel time by changing primers or powder charge, you can detune a load.

In most rifles, with bore line above the support point on the shoulder, that whip tends to be greatest in the vertical direction, so the effect of changing the barrel time is to add some vertical stringing to the group. The difference in Reloadron's groups #3 and #4 appear to be good examples of what to expect from that kind of detuning. The caution is that the 95% confidence range for 10 shot groups will span about ±20%, so confidence that the groups are truly not randomly different will be less than 95%, by eyeball. The t-test in Excel can be used to determine the actual confidence that they are not just randomly different, but the fact #3 is narrower than the other groups is strongly suggestive of a different position in the phase of the muzzle deflection.

I'll briefly reiterate something that's come up in past discussions. Many people don't seat primers well, and thus get less consistent results than they otherwise would. A primer is ideally seated by inserting it about two to four thousandths past the point where the anvil touches the floor of the primer pocket. This "sets the bridge" which is the thickness of priming mix between the anvil and the bottom of the primer cup. If you don't have a way to do this by measurement, the general advice from the late Dan Hacket is good to follow:

Several things can cause confusion on this topic. First, brissance does not mean primer power in the sense most people or the pendulum test discern it. That is, it doesn't determine the size or total energy of the flame or the quantity of hot gas or sparks produced, though it does affect its duration.

Brissance is tested by setting off a fixed quantity of explosive in sand that has been graded in specific mesh sifters to have no fine particles left. After the explosion, the sand is re-sifted using the finest grading mesh previously employed to see how much new fine sand broken down by the explosion comes through. So brissance is the sand shattering quality of the explosive. It is a measure of the suddenness of the explosion, as a more sudden explosion concentrates more energy in its wave front, and the higher that energy density the more abruptly it impacts solid matter and the more shattering ability it has.

One effect of changing primers is to change peak pressure. In 2006 in Handloader Magazine, Charles Petty ran the same 223 load (24 grains of RL 10X and 55 grain V-max; one grain over Alliant's listed maximum) with a range of primers and got muzzle velocity change of about 4.8% (3150 fps mean to 3300 fps mean velocity). In the latter case the powder was being lit up faster, giving it a higher equivalent burn rate, so it peaked sooner and higher, raising bullet early acceleration. Since velocity goes up directly with powder charge at typical rifle pressures, it was equivalent to the velocity effect of increasing the powder charge about 4.8%. However, to reach the same velocity from the smaller quantity of powder burning faster, the pressure peak goes up a bit more. In this case, the rough equivalent of a 5.3% increase in 10X powder charge, which produces about an 18.5% increase in peak pressure (from QuickLOAD model).

When you change how early in a barrel the acceleration peaks, even though the powder charge and therefore the muzzle pressure are close to the same, the bullet runs down most of the barrel with a faster head start. This means the barrel time is shortened. Load tuning typically produces sweet spots when the barrel time of a bullet and the pressure and recoil-induced whip of the muzzle are synchronized at a slow changing phase in the swing. So when you alter barrel time by changing primers or powder charge, you can detune a load.

In most rifles, with bore line above the support point on the shoulder, that whip tends to be greatest in the vertical direction, so the effect of changing the barrel time is to add some vertical stringing to the group. The difference in Reloadron's groups #3 and #4 appear to be good examples of what to expect from that kind of detuning. The caution is that the 95% confidence range for 10 shot groups will span about ±20%, so confidence that the groups are truly not randomly different will be less than 95%, by eyeball. The t-test in Excel can be used to determine the actual confidence that they are not just randomly different, but the fact #3 is narrower than the other groups is strongly suggestive of a different position in the phase of the muzzle deflection.

I'll briefly reiterate something that's come up in past discussions. Many people don't seat primers well, and thus get less consistent results than they otherwise would. A primer is ideally seated by inserting it about two to four thousandths past the point where the anvil touches the floor of the primer pocket. This "sets the bridge" which is the thickness of priming mix between the anvil and the bottom of the primer cup. If you don't have a way to do this by measurement, the general advice from the late Dan Hacket is good to follow:

"There is some debate about how deeply primers should be seated. I don’t pretend to have all the answers about this, but I have experimented with seating primers to different depths and seeing what happens on the chronograph and target paper, and so far I’ve obtained my best results seating them hard, pushing them in past the point where the anvil can be felt hitting the bottom of the pocket. Doing this, I can almost always get velocity standard deviations of less than 10 feet per second, even with magnum cartridges and long-bodied standards on the ’06 case, and I haven’t been able to accomplish that seating primers to lesser depths."

Dan Hackett

Precision Shooting Reloading Guide, Precision Shooting Inc., Pub. (R.I.P.), Manchester, CT, 1995, p. 271.

Dan Hackett

Precision Shooting Reloading Guide, Precision Shooting Inc., Pub. (R.I.P.), Manchester, CT, 1995, p. 271.

I'll briefly reiterate something that's come up in past discussions. Many people don't seat primers well, and thus get less consistent results than they otherwise would. A primer is ideally seated by inserting it about two to four thousandths past the point where the anvil touches the floor of the primer pocket. This "sets the bridge" which is the thickness of priming mix between the anvil and the bottom of the primer cup. If you don't have a way to do this by measurement, the general advice from the late Dan Hacket is good to follow:

"There is some debate about how deeply primers should be seated. I don’t pretend to have all the answers about this, but I have experimented with seating primers to different depths and seeing what happens on the chronograph and target paper, and so far I’ve obtained my best results seating them hard, pushing them in past the point where the anvil can be felt hitting the bottom of the pocket. Doing this, I can almost always get velocity standard deviations of less than 10 feet per second, even with magnum cartridges and long-bodied standards on the ’06 case, and I haven’t been able to accomplish that seating primers to lesser depths."

Shooting Times had a great article on primers, Mysteries And Misconceptions Of The All-Important Primer

http://www.shootingtimes.com/ammo/ammunition_st_mamotaip_200909/

The author, Allan Jones , explained why high primers were the most common cause of misfires, and it had all do with seating of the anvil and seating the bridge thickness.

This critical distance is known as the bridge thickness. Establishing the optimum thickness through proper seating means the primer meets sensitivity specifications but does not create chemical instability. However, failing to set the bridge thickness through proper seating depth is the number one cause of primer failures to fire. The bridge thickness is too great with a high primer, even one whose anvil legs touch the bottom of the pocket.

For proper ignition the anvil needs to be firmly set and then the cup pushed down to set the gap between cup and anvil. In between is the primer cake. Also, something not generally understood, is that firing pin offset is bad. The further from center the firing pin hits, the more likely a misfire or incomplete primer combustion. I had posters in in this thread Firing pin strike http://thefiringline.com/forums/showthread.php?t=527973&highlight=primer+offset tell me that firing pin offset was unimportant, and, some claimed that the firing pin could hit anywhere out to the edge and the primer would still go off. All such replies were an example of the Dunning-Kruger effect.

As David Dunning said in Pacific Standard Dec 2014, Confident Idiots

In many cases, incompetence does not leave people disoriented, perplexed, or cautious. Instead, the incompetent are often blessed with an inappropriate confidence, buoyed by something that feels to them like knowledge.”